With one leg stretched along the three-foot barre, I looked over at the floor-to-ceiling mirror and wondered if my teacher would tell me that my toes weren’t pointed. I leaned over, connecting my hand to my foot for the stretch I noticed all the other kids were already doing, absent-mindedly thinking about the splits test I was bound to fail and the choreography I had forgotten from last week. I looked over at my friend, noticed her toes were perfectly pointed, and corrected my own.

While dance seemed like a chore back then, as I got older I realized how much I cherished my dance classes and the memories and friends I made there. Students today are not having the in-person class experiences that made my childhood dance classes a large part of my life, manifesting into jobs and friendships that I have to this day.

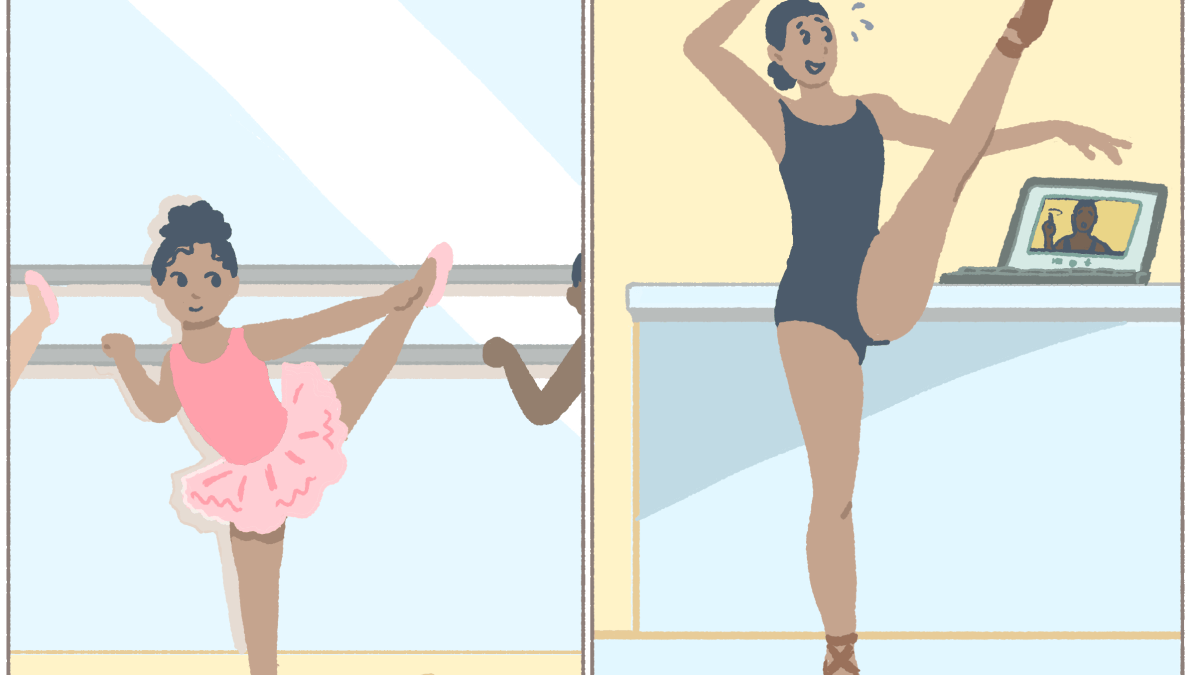

In the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, studio classes with friends have turned into Zoom extensions, with students alone in their garages pretending to be frozen to avoid complicated combinations. Not only does this mean dancers and dance schools are struggling, but the future of this art form may hang in the balance.

Roughly $15 billion has been lost by nonprofit arts and culture organizations, and 99 percent of performing or producing organizations have been forced to cancel events, according to the American’s for the Arts’ “COVID-19’s Impact on the Arts Research and Tracking Update” report in February 2021.

Among the wreckage of cancelled recitals and productions is Elaine’s Dance Studio, a local studio in Santa Cruz. Founder and director of the studio Elaine McCarthy was forced to close her doors in March 2020, around the start of the pandemic, but realized there were larger problems than just cancelling her performance at the end of the season.

“When we did Zoom classes, for my studio, we didn’t like it. The teachers didn’t like it, the kids didn’t like it, I had quite a few people drop [out],” McCarthy said. “In 35 years of teaching and having a studio, this has been the biggest challenge, keeping the studio afloat.”

With kids dropping out of dance, studios are struggling to remain open. For months, McCarthy has foregone her own paycheck, only able to afford paying her employees. McCarthy said that despite a discounted rent from her landlord, she is crossing her fingers that the studio can continue to operate.

These financial troubles extend past the walls of Elaine’s Dance Studio, with large dance and performing communities forced to cancel productions and shows in order to keep their performers and the community safe. The American Ballet Theatre (ABT) and San Francisco Ballet (SFB) both announced cancellations of upcoming 2021 seasons, with ABT cancelling its fall 2020 and spring 2021 seasons, and SFB announcing its full 2021 season would be virtual, after cancelling its productions since March.

Dance schools are struggling. Dance students are abandoning their passion for dance altogether. The productions and artists that once inspired young creatives are off the stage, only viewable through Instagram posts and virtual productions. So, what will the next generation of dancers really look like?

As university students can attest, Zoom can be exhausting. More than the aggravations of students, struggles of internet connection, or non-functioning cameras and microphones, Zoom makes dance class both complicated and frustrating.

In a traditional pre-COVID dance class, instructors closely monitor the positions and mechanics of a dancer’s motion, ensuring correct placement and their safety. When dancers occupy their garages as make-shift studios and teachers are watching them in small portions of a computer screen, it is certainly a change from the studio atmosphere.

It’s not difficult to imagine the complications of rehearsing the “Swan Lake” pas de deux alone in your concrete-floored garage, or execute a flawless grand jeté in your cramped childhood bedroom. If students cannot rehearse or practice their art form, how can we expect them to be the professional dancers we see in movies, musicals, performances, or teaching our children in the future?

This almost year-long break from in-person dance has caused students and performers to fall out of their rhythm of consistent classes, learning choreography, and adjusting to the bright lights of the stage. Without the proper education or training, amazing dancers and educators like Misty Copeland or George Balanchine would not have had the influence or cultural importance to the dance community that they do today.

The COVID-19 pandemic’s impact on the dance community cannot just be measured in the moment. COVID-19 is standing in the way of the performers of tomorrow, and will continue to do so until it is safe to meet in-person and students can yet again work in the uplifting community of performers, instructors, and audience members they long to return to.

Pas de deux: A dance for two people

Grande Jeté: Classical ballet term meaning, “big throw” in which a dancer leaps by springing off one foot, with the other extended in front of them.

Misty Copeland: The first Black female principal dancer at the American Ballet Theatre, advanced from soloist to principal in 2015.

George Balanchine: Collaborated in the creation of what would become the New York City Ballet and either partially or fully choreographed popular ballets such as “Firebird” (1949) and “The Nutcracker” (1954). Balanchine served as New York City Ballet’s artistic director until his death in 1983.

While my own dance career may have wavered, students who are destined for big things are not experiencing the training of a rigorous class, the attention of a strict artistic director, or the motivation from their peers they need in order to sustain the future of the dance industry.